Interview with Filippo Avalle

Why is the theme of the labyrinth central to your work?

My passion for the story of Minos and the Minotaur, passed down to me by my teacher Mr. Gibelli in fifth grade, then, a few years later, the adventurous game I played exploring (even if forbidden) the subterranean world beneath the Sforzesco Castle in Milan together with my engaging studies of the Classics in high school, all brought me to develop in my artistic career the dimension of the labyrinth. It has become one of the fundamental characteristics that still distinguishes the spatial structure of my works today.

So also “playing” has its influence: do you belong to the ‘Meccano kids’ generation?

In my generation Meccano was the construction game of choice by kids who enjoyed building things. For those who don’t know or remember it, Meccano was made of building boxes with various components like boards, plates, extrusions, angle brackets, all of varying sizes and shapes, in glazed perforated metal, that could be assembled and disassembled with nuts and bolts to make a wide range of constructions, with the aid of diagrams. That which attracted me most was the possibility of constructing self-propelled mechanisms with the assistance of small steam turbines. The first were developed in the wrought frameworks of methacrylate, the latter we can now say have been composed with the auxiliary electrotechnical mechanism used for lighting: fiber optics, LED and photovoltaic cells. There were also other construction games: model houses and sailing ships fabricated with cardboard, castles made of sand and huts put together with branches and twine, but now I’m starting to get lost in my memories… They were all games that sharpened my artisanal and design capabilities that are important in all artistic work.

Why is your concept of a “Bottega” so important for you?

I never had a real teacher who taught me “the trade” and served as my guide. Perhaps for this reason, I feel a greater need to transmit my experiences in this field of work to new generations. The meaning I give to ‘bottega’ is not limited simply to the idea of working together on a commission that requires extra “manpower” or specific skills, but it encompasses the transmission of knowledge in a shared vision of project-oriented and artistic objectives that are not necessarily one-directional (teacher-student). I have been fortunate to work in this way – in both my atelier and in the NABA workshop – with many artisans, professionals and students with whom I am still in contact today.

What does commissioned work mean for you?

Generally, I prefer to accept commissioned work rather than work for the art market because commissions come about thanks to a dialogue between client and artist and the result is the artwork. Working for clients who wish to satisfy their corporate image needs through an artistic interpretation brings about a stimulating comparison with new content, as well as the challenge of understanding how to represent these needs with a work of art. In my experience thus far, I’ve always encountered open minded and incredibly sensitive clients, who understood the artist’s necessity to operate freely and so, on my part, I have given importance to their indications, however rough they were. A similar rapport of reciprocal exchange can also be found with some gallerists and, here too, I consider myself lucky in my experiences. A good gallerist does not order a serial production in terms of subject, number and size, but observes, first and foremost, that which the artist is capable of doing within his personal research. Sometimes, in an initial phase, there can also be an investor who assumes a proactive role for the market.

Why has Lucio Fontana been your point of reference since the beginning?

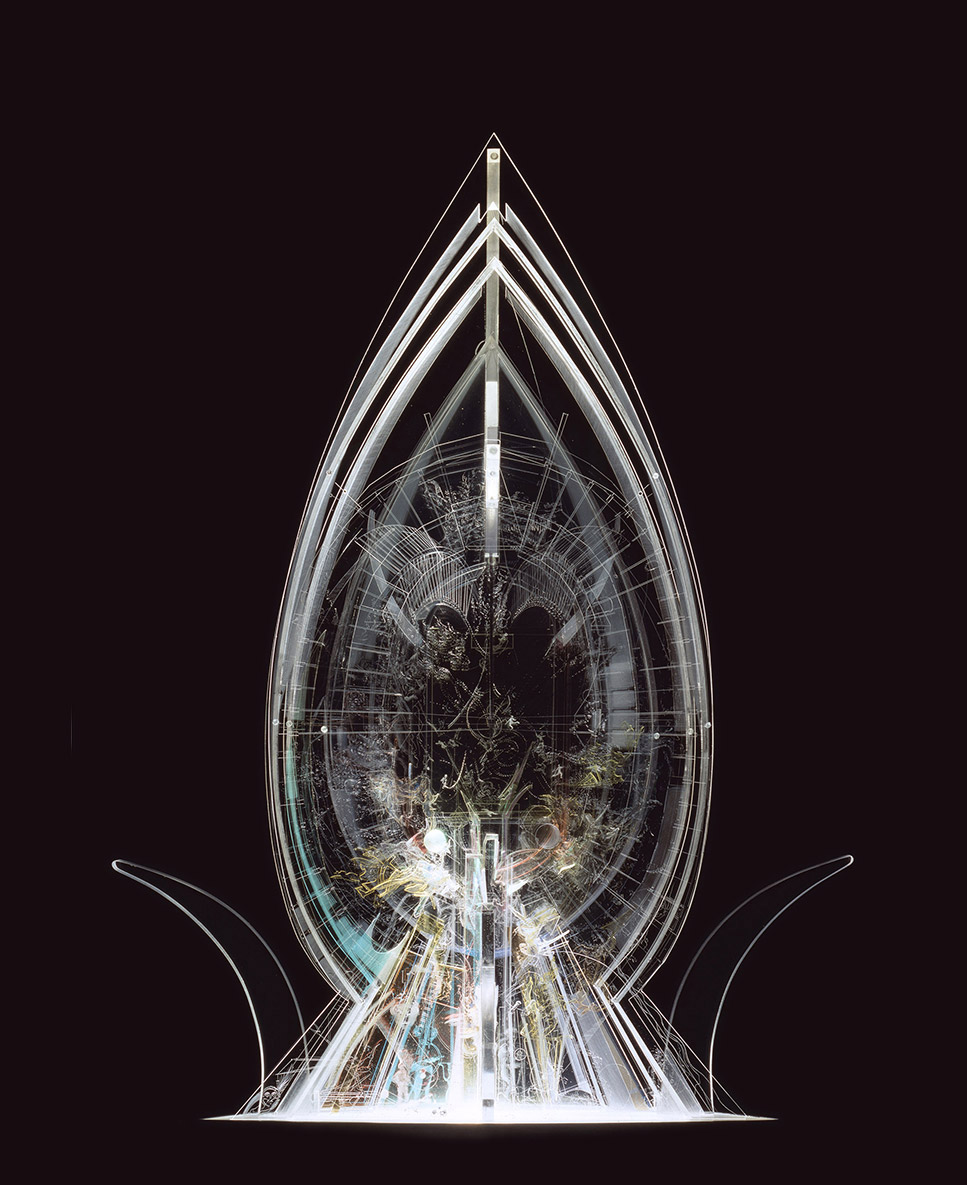

Ever since Lucio Fontana, by slashing a cut into the canvas, marked the adventurous transition from modern to contemporary art, he indicated to me the road of exploring a space that went beyond the traditional one. I thus set off on a complex but liberating research. The slashed canvas (“cuts”) invited me to surpass the flat surface and explore a space “beyond”. It was not merely about transitioning to the third dimension of sculpture, but introducing a stratified dimension that could unite painting and sculpture. A stratification of solids and hollows, made of layers of etched plexiglas combined with incredibly thin elements of the same material placed in between each plane. The ever-changing space created by this stratification inside the transparencies and opalescence of plexiglas allows for those who look at the piece (myself included) to undertake a journey of discovery. At the present moment, I am exploring a different possibility of vision given by Fontana’s “cut”, one which accepts the “wound” of the plane and exposes the interior elements, outlines engraved with a scalpel among extremely thin sheets of polyester. The viewer is almost tempted to touch them. I am once again at the beginning of another course of research so I cannot disclose more for now.

Seeing some of your more recent works, in particular the pastel drawings, could we say there is a return to two-dimensionality?

They appear two-dimensional because executed on a flat surface, but here too there is a stratification – made of marks and shades of color – that confers to the pieces a perceptible multidimensional trait.

What does “Opera Unica” (All One Artwork) mean?

“Opera unica” (All One Artwork) stands for the entirety of my artistic production, with a pull towards constant research and renewed integration of all resources of painting, sculpture, architecture and lighting design. The focus is on the progressive creation of a complete work of art, made of more than one section, each of which contains several parts. The works in these sections are interdependent and confluent, made of an intrinsically dynamic and aggregative nature. They are connected by recurring themes and researches that act as a common thread, such as the labyrinth, organic and visionary architecture, individual and social dynamics and, from a technical point of view, light as material. With “Opera Unica” (All One Artwork) I do not think of a totality that consumes itself in its intentions, or that that closes itself in an encyclopedic whole, or in an infinite potentiality that proves to be inconclusive. Instead, I think of an Artwork that emanates strength and energy in virtue of its own vitality and the integration of disciplines without taking away anything from each of them.

Sacredness, spirituality and religion are all aspects that your work explores. Is there a relationship with the laic dimension and, if so, how would you describe it?

In my early work, I paid much attention to the sacred and even more so to a spiritual dimension. For example, “L’incidente” (The accident) represents a car accident with the classic composition of the Deposition of Christ: recalling a formal religious layout was a style utilized to narrate a non-Christological theme. Since 1992 there have been a few commissions like “Crocifissione” (Crucifixion) for the chapel of the Costa Allegra cruise ship, then “Via Crucis” for the Nuova Chiesa in Montegrosso, and “Ultima Cena” (Last Supper) as part of the exhibition “Ultime ultime cene” (Last last suppers) at Palazzo delle Stelline in Milan. Explicit spiritual contents can be found in my small piece on Gandhi. In my work, however, the sacred, although I should probably speak of spirituality, is always connected to laicism and today’s human reality. The stations of my “Via Crucis” serve as an example, where the image of the Cross is the result of the intersection between an airplane and a tower in New York.

What do you see as the opportunities in this day and age?

We live in an age that distinguishes itself for its accelerated and diversified development in the scientific and technological field. The central problem, however, is how to manage these resources. Culture and so also art are precious and decisive instruments for the choices that will need to be made for the future. Politics and the business world should take this into consideration and reflect carefully on it.

What are your present artistic “worries”?

For those who, like me, live in Europe, in a society that justifiably compares itself more and more with other realities, it is essential to examine the themes involving the abuse of power at the expense of freedom of thought and fundamental human rights. As an artist, my formal choice to use the technique of stratification of images offers the viewer the possibility to become first an observer and then a free interpreter of this reality.